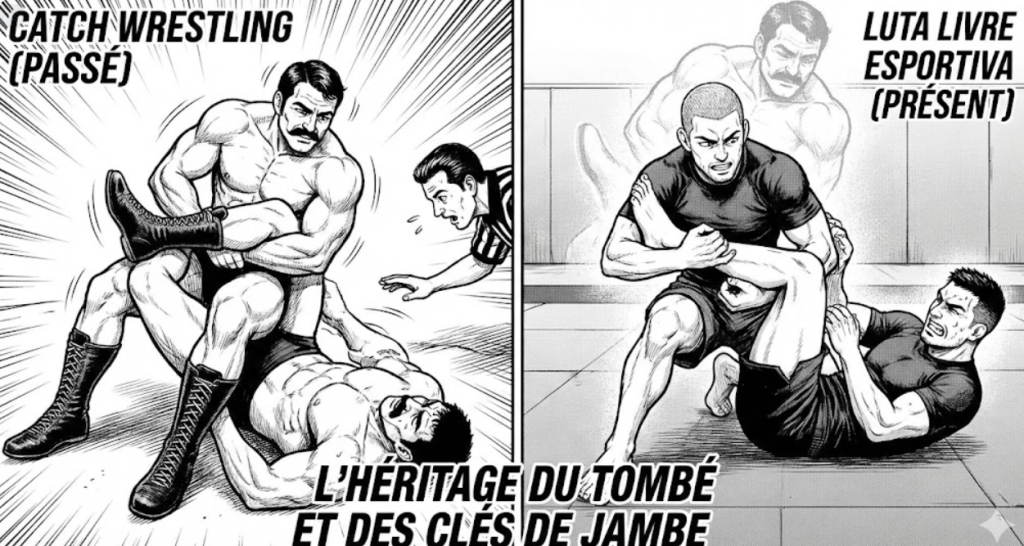

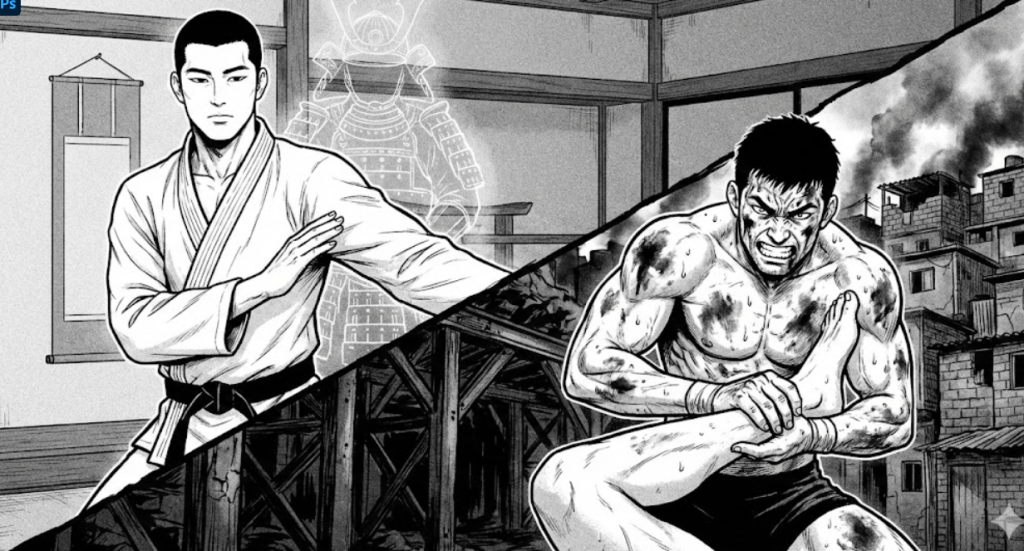

Mon intention cette saison est de retourner aux sources de la Luta Livre de Tatu. Pour ce faire, j’étudie dans un premier temps la forme de Catch Wrestling de Wigan, pour ensuite passer à celle des USA, la mère de la Luta, et enfin à celle du Japon, avec le Shooto.

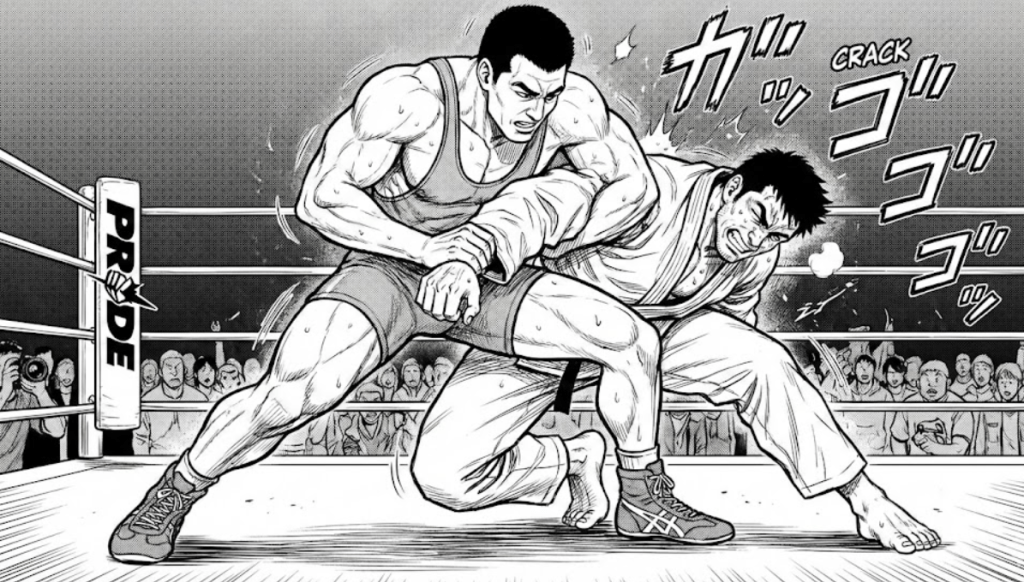

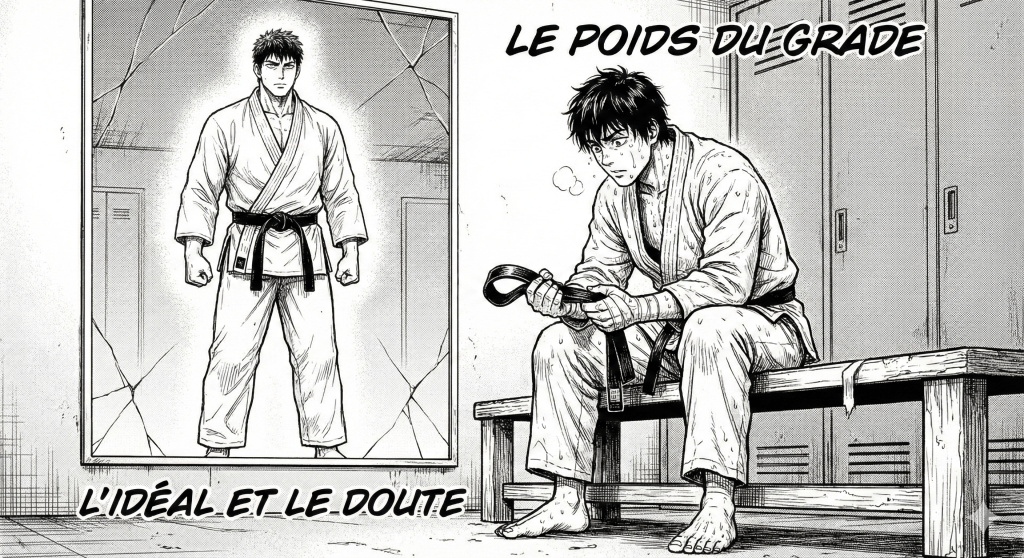

Cependant, une chose est complexe : intégrer un système qui ne pense pas comme ce que nous étudions depuis 30 ans, ce grappling formalisé à travers le Jiu-Jitsu. D’ailleurs, notre façon d’enseigner les techniques, même si le « rebranding » américain est maintenant Jiu-Jitsu, en tant que professeur, donne un enseignement qui reste assez souple, avec des transitions marquées par une certaine fluidité.

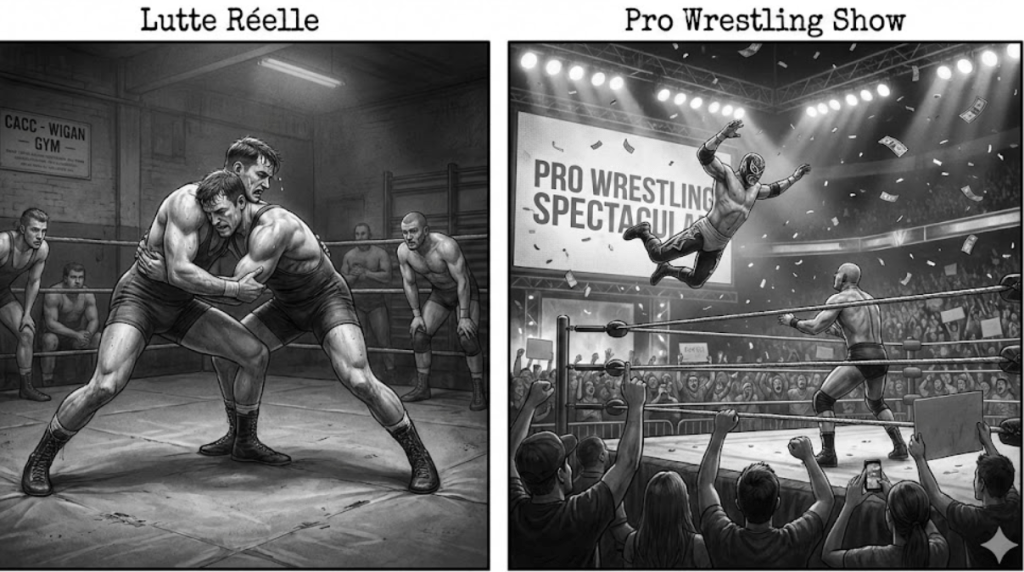

En Catch Wrestling / Luta Ancienne (CWLA), tout est séquencé avec l’utilisation de la douleur comme un levier nécessaire dans l’exécution des techniques. Ce qui donne une impression de « bourrinage » et que rien ne se fait de façon fluide. De plus, à l’inverse du grappling, il y a beaucoup de décrochages. C’est un peu comme si, en Jiu-Jitsu, on s’adaptait à l’opposant, on gardait le contact pour rester dans une séquence, alors qu’en CWLA, on pense à toujours se relever.

Ce n’est pas une fuite, mais il y a une préférence à lâcher une posture qui n’apporte rien en se « dégrafant » pour récupérer soit debout, soit sur un équivalent « à genoux ». Ce sont des situations dont nous, grapplers, ne sommes pas fans, voire que nous pouvons considérer comme de l’anti-jeu.

Seulement, c’est cohérent avec cette idée d’éviter de rester dessous et, inconsciemment, de subir des takedowns. Se redresser et chercher à retrouver une posture neutre, souvent en lutte, est préférable à recomposer une garde et de « sweeper ».

Dans une démarche de vouloir intégrer au sein de la forme de Luta Livre que Flavio m’a transmise, tout en respectant des concepts plus CWLA avec ce qu’est devenu le grappling actuel, il y a beaucoup de choses qui ne semblent pour l’instant pas vraiment compatibles et qu’il va falloir que je parvienne à intégrer pour l’enseigner dans le jeu de mes élèves…

Prenez ce qui est bon et juste pour vous. Be One, Pank.

—

Martial Reflections of an Hypnofighter #503: Integrating Catch Wrestling into Modern Grappling

My intention this season is to return to the roots of Tatu’s Luta Livre. To do this, I am initially studying the Wigan form of Catch Wrestling, then moving on to the USA’s form, the mother of Luta, and finally Japan’s, with Shooto.

However, one thing is complex: integrating a system that doesn’t think like what we’ve been studying for 30 years, this grappling formalized through Jiu-Jitsu. Moreover, our way of teaching techniques, even if there’s been an American rebranding to Jiu-Jitsu, as a teacher, results in a fairly flexible instruction with transitions marked by a certain fluidity.

In Catch Wrestling / Old Luta (CWLA), everything is sequenced with the use of pain as a necessary lever in the execution of techniques. This gives an impression of « brutality » and that nothing is done fluidly. Furthermore, unlike grappling, there are many disengagements. It’s a bit like in Jiu-Jitsu we adapt to the opponent, we maintain contact to stay in a sequence, whereas in CWLA, the thought is always to get back up.

This isn’t an escape, but there’s a preference to abandon a posture that offers nothing by « disengaging » to recover either standing or in a « kneeling » equivalent. These are situations that we grapplers are not fond of, and we might even perceive them as anti-game.

However, it’s consistent with the idea of avoiding staying underneath and, unconsciously, suffering takedowns. Getting back up and trying to regain a neutral posture, often in wrestling, is preferable to recomposing a guard and sweeping.

In an effort to incorporate elements into the Luta Livre form that Flavio passed on to me, while also respecting more CWLA concepts within what modern grappling has become, there are many things that currently don’t seem truly compatible and that I will have to succeed in integrating to teach them in my students’ game…

Take what is good and right for you. Be One, Pank.