Nous le savons tous, la projection, à l’inverse du takedown, a pour but de percuter le sol. Nous savons que tomber est une chose dangereuse pour tous les combattants, soit parce qu’il peut y avoir une avalanche de frappes après, soit parce qu’un adversaire gère le sol, soit parce que nous pouvons être blessé et difficilement continuer à nous défendre.

C’est le cas de ce combat de championnat que nous avons eu cette nuit, avec le bras qui semble s’être disloqué (le combat vient de se finir, nous n’avons pas d’informations pour le moment), et donc le combat s’est terminé sur abandon. Si vous regardez souvent le MMA, il y a peut-être une chose qui vous marque depuis des années : la tension que beaucoup de combattants mettent sur leur bras pour scrambler directement et ne pas rester au sol.

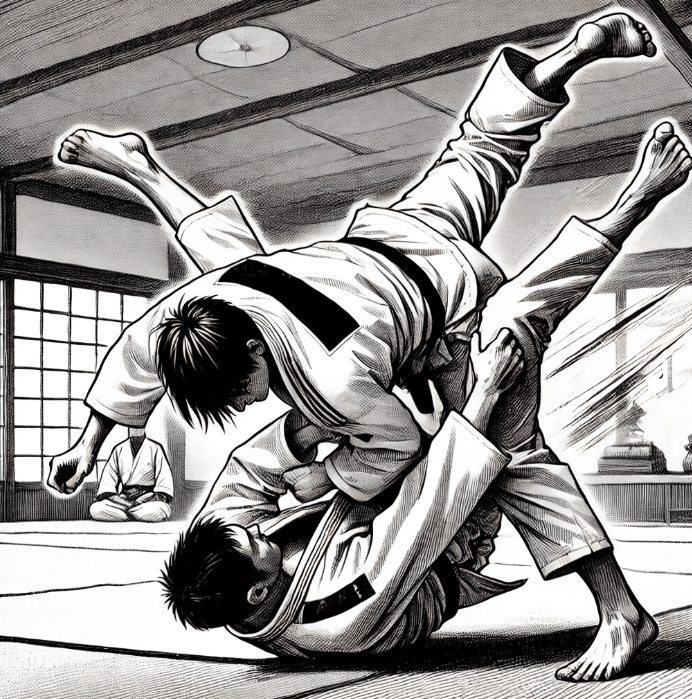

Et si nous savons une chose dans les ukemis, c’est d’absorber plutôt que de bloquer l’impact. Le souci, sur des angles moins courants, c’est que notre corps ne supporte pas la pression sur le membre ou la partie qui est impactée au sol. Le match de Merab est en cours et il se fait casser par Yan. À un moment, Merab lève complètement son opposant et le met sur l’épaule pour le planter au sol.

Seulement, ce type de projection attendu et sur un sol de cage n’est pas assez effectif pour empêcher son opposant de tranquillement se relever et retourner en pied-poings. Nos lutteurs, samboïstes ou judokas en MMA ne parviennent pas toujours à faire mal sur la projection, parce que parfois l’impact recherché ne donne pas de résultat et l’effort effectué n’amène pas de contrôle ou de position forte.

C’est vraiment une arme potentiellement intéressante mais pas assez peaufinée pour la cage ou même le grappling, où les hors-combats sur projection sont très rares.

Prenez ce qui est bon et juste pour vous. Be One, Pank. https://www.passioncombat.net/

—

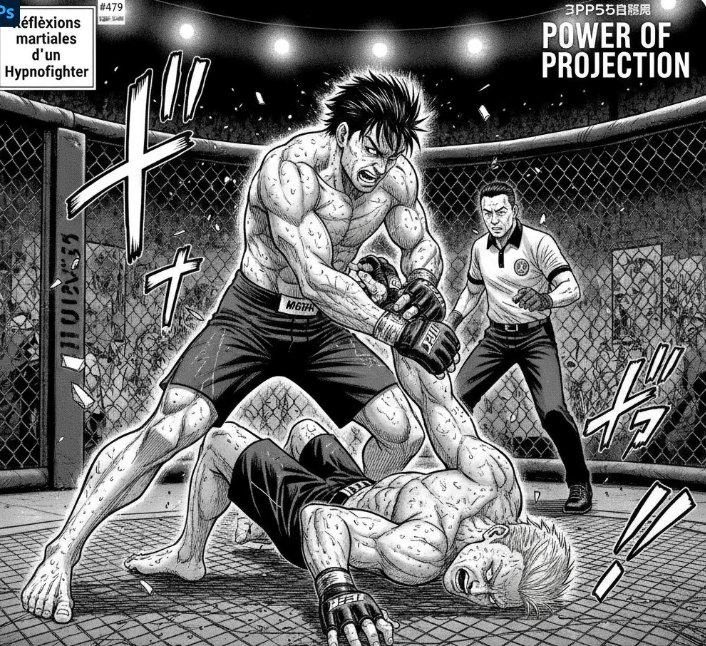

Martial Reflections of an Hypnofighter #479: The Power of the Projection

We all know that projection, unlike a takedown, aims to hit the ground. We know that falling is a dangerous thing for all fighters, either because there can be an avalanche of strikes afterwards, or an opponent who controls the ground, or because we can get injured and find it difficult to continue defending ourselves.

This was the case in the championship fight we had last night, with the arm appearing to be dislocated (the fight has just ended, we have no information for the moment), and so the fight ended in a submission. If you often watch MMA, there might be one thing that has stood out to you for years: the tension that many fighters put on their arms to scramble directly and not stay on the ground.

And if we know one thing in ukemis, it’s to absorb rather than block the impact. The problem, with less common angles, is that our body cannot withstand the pressure on the limb or part that is impacted on the ground. Merab’s match is ongoing and he’s getting broken by Yan. At one point, Merab completely lifts his opponent and puts him on his shoulder to slam him to the ground.

However, this type of expected projection on a cage floor is not effective enough to prevent his opponent from calmly getting back up and returning to striking. Our wrestlers, Sambo practitioners, or judokas in MMA do not always manage to inflict damage with a projection, because sometimes the desired impact does not yield results and the effort made does not lead to control or gaining a strong position.

It’s really a potentially interesting weapon but not refined enough for the cage or even grappling, where knockouts from projections are very rare.

Take what is good and right for you. Be One, Pank. https://www.passioncombat.net/